Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

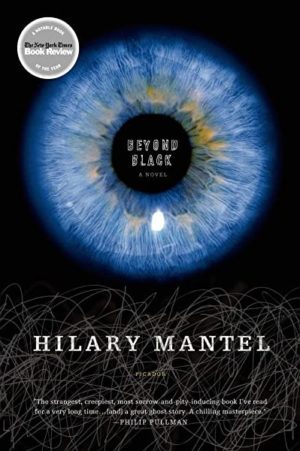

This week, we continue Hilary Mantel’s Beyond Black with Chapter 11. The novel was first published in 2005. Spoilers ahead! CW for slurs related to ethnicity and gender, and abortion treated as a shameful secret.

“But the strong thing about airside is that it has no rules. Not any we can understand… And the bottom line is, Colette, there are more of them than us.”

Alison can understand why fiends would be drawn to Admiral Drive, what with all the diggings, men going about men’s business, and trenches where things could be concealed. But Colette has Alison online, emailing predictions around the world. She’d like to make Alison a global brand, like McDonald’s, only not so fattening. The weather alternates between oppressive heat and drenching storms. Alison’s crystal ball fills with “shifting cloudbanks, as if it were making its own weather.”

Silvana recruits Alison to do team psychic event. Alison doesn’t tell Colette that Silvana initially skipped her because no one can stand her “snotty” manager.

A male presence begins to haunt the house. Small items go missing. Someone makes a mess in the kitchen overnight—not Alison cheating on her diet, though Colette would never believe her. A man’s sock appears in the washing machine. Colette thinks Mart. Alison fears Morris.

The Fig and Pheasant, once a coaching inn, nowadays features “vaguely William Morris wallpaper” and a raucous Sports Bar. The psychics will perform in a repurposed function room. Each plans a twenty-minute stint, with Colette handling the in-audience microphone. While Mrs. Etchells waits her turn, she complains that Alison never calls her “granny.” Gemma opens the demonstration tough, bullying the audience into quick answers. Etchells goes next.

As usual, she first describes a Spirit World full of love and joy, then focuses on an older woman with vague physical complaints. Things turn weird when a spirit crudely suggests that the woman has been miraculously knocked-up. The backstage psychics grow uneasy, the audience hostile. Next Etchells focuses on a man in the back row only she can see, a fellow who’s replaced his missing eye with a false one. He’d be MacArthur, she later recalls. Keith Capstick is there, too.

Alison goes out to rescue Etchells, who begins reminiscing about how Alison got punished for playing with knitting needles. Didn’t she know those were her mother’s for use on the fiends’ girlfriends? She tried to abort Alison, too, but Alison was a stubborn fetus. Finally Alison gets Etchells backstage. The old gang’s all out there, Etchells says: MacArthur, Capstick, Bob Fox, except “they’ve got modifications”—something “you wouldn’t want to see in a month of Sundays.” Alison asks about Morris but gets no answer. The other psychics argue about how to get the obviously ill Etchells to a hospital, and who should face the restless audience. As Etchells rants on about her prostitute daughter, Alison takes the stage and gets the show back on the road. In the back row, she sees “a faint stirring and churning of the evening light.”

An ambulance carries Etchells off. On the drive home, Alison tries to explain to Colette why she has an evil spirit guide. Some people are truly “nice” and have lovely thoughts that lift them to a higher spiritual level. Others have “gone rotten inside” from thinking about things the “nice” people never have to face. The latter attract “low entities” like Morris and crew, who feed off the damage they’ve suffered. Alison has struggled since childhood to have “nice” thoughts, but her head is too “stuffed with memories.” She tried to “do a good action” by helping Mart, but Colette wouldn’t let her. The fiends want Alison because without her they can’t exist. Colette’s unimpressed by these revelations.

On Admiral Drive, Pikey Paul, Etchells’ spirit guide, waits weeping. Etchells has died, but Paul says she left messages on Alison’s tape recorder. A message from Mandy confirms the death. Alison turns on the recorder and has a two-way conversation with her grandmother. What’s Spirit World like? Like Aldershot, back when Alison’s mother would stagger home with her latest john. Alison asks her to look behind the house. It’s rough ground and ramshackle sheds, Etchells reports, and a parked van. Directed to look inside the van, she describes a blanket wrapped around something, and a hand “peeping” out. No, it’s not Alison’s “chubby baby hand,” it’s a grown woman’s. Also, Keith Capstick has a message for Alison: He’s got his balls “armour-plated” now, so Alison won’t “be able to get at ‘em this time,” whatever sharp implement she wields.

Colette wants to talk about the inevitable funeral. Alison has to go out for “a breath of air.” The garden is dark. Neighbor Evan comes over with a flashlight. Someone was “snooping” around Alison’s shed earlier. Constable Delingbole checked it out, found nothing, but you can’t be too careful with tramps, can you?

Alison hears a low chuckle behind her. When Evan leaves, she turns to a large terracotta pot. Don’t play “silly beggars,” Morris, she says, and from the “very depths of the pot” comes a scuffling and another chuckle, “faintly muffled by the soil.”

This Week’s Metrics

What’s Cyclopean: Stormwater runs down the door in “scallops and festoons”.

The Degenerate Dutch: Mrs. Etchells, or possibly Keef talking through her, manages a quick paragraph denigrating Al’s mother not merely for being a prostitute, but for sleeping with circus dwarves and Romany and “god forgive her, foreigners.” The Neighborhood Watch knows how to prevent that sort of thing, patrolling their development for “any poor wastrels or refugees who had grubbed in for the night.”

Libronomicon: Merlyn’s book has gotten published, and he’s “gone to Beverly Hills.” This is probably not a euphemism.

Anne’s Commentary

Believe it or not, the Aldershot fiends have learned something during their “course”. It’s the same thing the best weird fiction writers learn: A horror jumping out without warning is scary, but more terrible is a horror that takes a subtler approach, creeping in at the edges of its victim’s perception, slowly stretching their nerves to the snapping point, like overtuned violin strings.

It’s worse for Alison because she knows what all the little intrusions portend. In truth, she’s been waiting since Morris left. Let her bask in the sunlight of his absence, denying the darkness always at her back. At the back of her mind, that is, those intractable memories which draw fiends in the first place, those unhealing sores they exist on, flies on carrion ever self-regenerated.

The fiends’ opening volley is a conversation between Morris and Aitkenside, playing on Alison’s recorder when she returns from a psychic “hen party.” As usual, Colette hears only white noise, but like a reader accustomed to run-of-the-mill deployments of the trope, she assumes the fiends are issuing threats. No, Alison says, they’re discussing the pickles you could get in the good old days. And remember how Bob Fox would torment MacArthur with a pickled egg, pretending it was MacArthur’s lost eye. Whatever happened to old Bob, who used to tap on the kitchen window to come in?

By making pickles the topic of the fiends’ chat, Mantel scores a comic triumph. Additionally, its randomness lets Alison credit Colette’s suggestion it’s just a “cross-recording” from before Morris’s departure.

Then Mart, who might be mad enough to see ghosts, tells Alison about a man who was looking for her. There were boxes in his unmarked van, but the man didn’t leave any.

Next comes late-night tapping on the kitchen window, like Bob Fox’s old knock, and Alison sees “fugitive movement” in the yard. It could be poor Mart, or she could be imagining it. She doesn’t want to be “premature.” Then drops a single portentous word, “But.” Placed at chapter close, it dangles in white space, ready to fall.

Meanwhile on Admiral Drive, there are the portents of heat and storm, shifting earth, black slime bubbling up drains, poisoned playgrounds. Naturally the developers bring in construction teams to rectify matters, but won’t such activity draw fiends?

Signs of a manly presence in the house multiply. Alison misses personal items like nail scissors and migraine pills. She catches whiffs of tobacco and meat. The signs grow more pointed. The apricot silk with which Alison always drapes her promo poster disappears; without it, Alison sees her own image as strange, as outdated as the other psychics claim. Talk about identity theft. Then someone violates Colette’s “precious” omelette pan, leaving it on the stove encrusted with grease and fried egg. Colette blames Alison, then Mart—who but Mart could also have left a hole-riddled sock in their washer? Alison doesn’t defend herself. She’d rather take the blame than admit that Morris and crew are slipping back into their domestic sanctum. Let Colette have the comfort of disbelief while she can.

The psychic tag-team provides the fiends with a perfect stage for their next escalation. The obvious authorial ploy would be for Alison to see her tormentors and perhaps to collapse. Mantel chooses to prolong suspense by electing Mrs. Etchells to see and identify them in all the horror of their “modifications,” while for Alison they remain a “faint stirring and churning,” just plausibly a trick of the evening light. Still more masterfully, Mantel uses Etchells’ fiend-inspired memories to verify the traumas that Alison’s been struggling to repress. Emmeline Cheetham was an out-and-out prostitute. She was an abortionist, too, taking care of the fiends’ inconvenient troubles. Alison was the one abortion she failed to pull off.

Homeward bound after the catastrophic evening, Alison clings to the banks of denial. She makes a (little-attended to) confession to Colette about why her spirit guide is evil, but she’s too scared to name the fiend she believes possessed Etchells on-stage, tellingly the one fiend Etchells didn’t name.

Etchells remains the fiends’ instrument after death. Pikey Paul, her spirit guide, pauses enroute to his next assignment to tell Alison her “granny’s” left a taped message. Alison’s recorder functions as an interworld telephone, allowing granddaughter and grandmother to converse in real time. Newly passed, Etchells has landed in Aldershot—to Alison’s dismay, there’s been no cleansing, no gentrification, in the Spirit World version, implying that when Alison passes, she may also end up in the Aldershot of her nightmares. The back of Emmeline’s house remains rough ground studded with dilapidated sheds, dog runs—and a van.

Inside the van, Etchells sees the blanket-shrouded corpse that may be Gloria. The capper: she delivers a “special message” from Keith Capstick. He’s got his balls armor-plated now, so Alison won’t be able to get at them this time, let her “hack away all bloody day, with [her] scissors, carving knife or whatever [she] bloody well got.”

The dead don’t forget the wrongs done to them in life, or the bloody justices either.

Gone outside for air, Alison instead receives the fiends’ coup de grace. Evan informs her there’s been an intruder snooping around her shed. The resulting tells Alison that Mart’s not the culprit. She knows that chuckle. Evan gone, she calls the chuckler by name.

The worst has happened, or the start of the worst. Morris has come home.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

So much plot development this week, without moving one inch the claustrophobic sense that nothing can change, nothing can be left behind.

Al is a survivor, starting before her birth when her mother couldn’t manage a back-alley (back-of-the-house) abortion, and continuing through a childhood of assault and trauma, and an adulthood of Morris and Colette and whoever else has cared to make her life hell. She’s good at survival. Escape, on the other hand, she’s only accomplished once: leaving her mother and the living fiends back in Aldershot. Now she learns, from Mrs. Etchells, that even is only a temporary reprieve.

Al is always drawing tarot cards, but this week’s spread seems particularly salient. First comes the Two of Pentacles: the instability and uncertainty of self-employment. Next the Four of Swords: the internet, crowds, and mass appeal. Together, these suggest the innovative new business proposition of Team Psychics—and the risks that come with a new venture.

The next card is the Two of Cups, which Colette glosses as a partner—“a man for me.” But Al notes that this reading, technically for her partner, is short on major arcana, as if “Fate wasn’t really bothered about Colette”. Al should be bothered, because her colleagues are blunt that they work with Al—sometimes—in spite of Colette’s abrasiveness. Colette doesn’t have a fate of her own, only the slender satisfaction she gets from her control over Al. Al’s never gotten anything better from a partner, and Colette looks almost acceptable in contrast to Morris. “A man for me,” indeed.

Then there’s the Papessa—I think this is the card I know better as The Moon. Several meanings are listed: a woman alone, hidden things making their way to the surface, patience leading to the revelation of secrets—and birth, and all the ways it goes wrong. All of these come up in Mrs. Etchell’s ill-fated session. Reversed, it can suggest that “problems go deeper than you think.” It can also suggest a female enemy, but the book points out that it doesn’t identify said enemy. Colette is the obvious choice, but she’s both obvious and—as previously pointed out—neglected by the major arcana, thus probably not symbolized by one. Who, then? Al’s unlamented mother Emmeline, perhaps? A true and deep enemy, past or otherwise.

Al, stuck with Morris for so long, has a talent for dealing with airside’s worst while keeping things palatable for audiences. Mrs. Etchells—her granny, though the relationship has stayed below the surface until now—has no such practice. Not only does she pass on every snide insult, but the fiends bring out her worst thoughts and better-glossed truths, from suspicion of her friends to crude insinuations about clients to Al’s sordid family history. It’s enough to kill her, and yet Al’s able to recover the show and the audience, get the patter back on track, and keep the night from being a complete disaster at least on the business side.

Al’s convinced that the fiends come to her because she’s damaged and traumatized. That may be so, but they may also come to her because she can survive them. That sucks—the fact that you can survive something doesn’t mean you should have to tolerate it. But neither she nor Colette gives any thought to the sheer level of strength and resilience demonstrated by her survival. By her ability to still “do a good action” even when all she sees is her failures.

And then Mrs. Etchells speaks to her from airside, to report that it’s all waiting for her after death, unchanged. The house, her mother, Aldershot. Torn down and replaced with the clean lines of capitalism in the living world, but inescapable in the long run.

Worse, maybe not entirely unchanged after all. What kind of modifications have the fiends gained from their course? And who is the dead woman in those packages that Al didn’t want to think about, fed to the dogs behind the house?

Is that where the enemy arises?

Whatever walks there walks alone—but it might like some company, if only they can follow the rules. Join us next week for Arkady Martine’s Rose House novella, recently released from Subterranean Press.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of A Half-Built Garden and the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon and on Mastodon as [email protected], and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.